Air Quality

By Michael FaginAir QualityWith 0 commentsAir Quality is impacted from forest fires, and the resultant smoke carbon released.

Wildfires and poor Air Quality

The Pacific Northwest and much of the West Coast of the US continues to go through a very bad fire year with considerable degradation to our atmosphere and air quality over a vast area. It seems appropriate to ask just how much our air quality was affected.

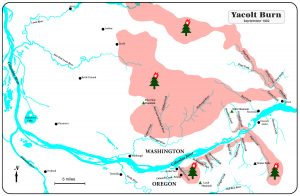

How bad was this summer’s fire season compared to others? Pretty bad is the instant answer but not the worst in the last 100 or so years. According to data from the Puget Sound Air Quality Monitoring System Early August 2017 had 85 PPM of particulates. With data from 2000, the previous high was 65 PPM in August of 2004, a very significant difference. While collection of this data is fairly recent the Yacolt Fire, in southern Washington of 1902 was much worse. Anecdotal information states that streetlights came on at noon in Seattle because of thick smoke and ships entering the Columbia River had to navigate by compass rather than using visual observation.

Air Quality and Yacolt fire

Washington State didn’t have a record number of acres burned, although British Columbia did. Temperatures were higher on average, but not at record highs. Both the precipitation and drought indices were within seasonal norms. So, what brought us all the smoke?

From an examination of Pacific Ocean weather patterns it appears that an anomalous high pressure ridge west of the Rocky Mountain Range trailing southwest to off the Pacific Coast of California combined with a deep low pressure trough over the Gulf Of Alaska to leave the Northwest with stagnant air. Also with sinking warm from the high pressure the smoke and particulates were forced to very low levels and at times close to ground level. Winds aloft also brought the ash at times from the fires in British Columbia. Thus Puget Sound Basin as well as areas of Central Washington experienced periods of poor air quality .

Fires additionally release large amounts of carbon dioxide, CO2, carbon monoxide, CO, and methane, CH4. All are greenhouse gases and are quite harmful to humans. All may increase vulnerability to respiratory ailments. CO2, is vital to life but can also be too much of a good thing. These gasses are less obvious to the immediate observer but are no less present in large quantities.

Most of the fires were ignited by lightning, especially in Washington State, but human caused fires raged in several areas and in Oregon especially. The fire in the Columbia Gorge being a prime example of careless behavior. Some in the environmental communities also point to the earlier policy of fire suppression as being a human contribution as it allowed for the growth of the undergrowth which provides much fuel to fires.

Impacts of past fires from other parts of the world

The 1997 fires which swept across Indonesia released between 13 and 40 percent of the carbon emissions worldwide for that year. These forests also had grown on a thick, up to 20 meters, layer of peat. This also burned, adding megatons of greenhouse gases

Further study also indicates that after a fire is extinguished carbon continues to leach into the atmosphere as the ground vegetation decays. The great forests of the planet are reservoirs of carbon. As the forests absorb carbon, which facilities growth, that carbon is held to allow photosynthesis to continue. The destruction of the forest releases not only the carbon, and other greenhouse gases, by combustion, but also releases the stored carbon from the forest floor. The cumulative effect is devastating as it may take decades, if not centuries to rebuild that carbon sink.

Forest fires will always be with us. They are a fact of life on the planet. Prescribed burns, of areas to clear out the understory is one example of minimizing the effects of fire. Reforestation, is also helpful but the mix of trees needs to be carefully monitored so as to not create monocultures of trees. This leaves those forests vulnerable to insect attacks and loss of viable trees. In addition, a more diverse forest expands the opportunities for wildlife to thrive.

Written by Robert Morthorst. We like to thank Professor Cliff Mass (University of Washington) and Puget Sound Clean Air Agency for some of the data.